New Publication in The Rumen

Check out my essay on writing poetry with a group. It was published by The Rumen, a great literary journal.

Check out my essay on writing poetry with a group. It was published by The Rumen, a great literary journal.

Binging a television show during quarantine is a subtle art. The show’s characters need to have an interesting enough life to keep you engaged and give you an escape from your current predicament. While they and their situation must be interesting, it can’t be too exotic, interesting, or enviable, otherwise you risk rendering too palpable the difference between the television show and your life stuck at home.

Those guidelines will keep you within a range of television shows that are comforting, but you need one more crucial filter to find a bingeable show while stuck in your home. That is, the show must have stakes high enough to build tension but not so high that you burn out your attention with one or two episodes.

Only a few shows available on the major streaming services thread this needle. Of those, I have recently been watching through, Gilmore Girls might be the best of the group.

Before beginning an analysis of why it is perhaps the best, readily available binge TV, let’s get a synopsis out of the way. How does it work? Why does it work?

Gilmore is essentially a wish fulfillment fantasy of a near perfect mother-daughter relationship. The two main characters Lorelai and Rory are a symbiotic dyad, as much best friends as parent and child. Their bond is deep and good natured and genuinely loving. That bond alone wouldn’t make for great storytelling, so it is contrasted with the mother-daughter relationship between Lorelai and her mother Emily, a cold and controlling woman obsessed with the expectations and mores of high society.

That is all to say that the majority of the show is an examination of intra-female communication. There are boyfriends, potential boyfriends, fathers, and male townies who populate the show as well, but the major characters and connections are all female.

That female-based generational drama is further exacerbated through a class dynamic that runs through the show. Lorelai left the world of her wealthy parents, but daughter Rory — being a privately educated, Ivy League bound teenager — has no need to rebel against her grandparents. That closing of the loop (the granddaughter bridging the family schism between the grandmother and mother) causes conflict and context for much of the show.

The class elements make for smooth going. The problems are by and large non-problems. An entire episode is devoted to Rory’s struggle over which college to attend: Harvard, Yale, or Princeton. Lorelai’s origin story is one of a brave rich girl deciding not to be rich. While one could wax Marxian about the ideological effects of encouraging people to sympathize with the bourgeoisie, one can’t say it makes the show bad binging fodder. Returning to the earlier point of not-too-high-but-not-too-low stakes, rich people’s non-trauma based family drama is perfect to hit that note.

After all, we all have families, so we can sympathize with not getting along with our uptight mother or trying to support your well meaning teen through the hard times of adolescence. But the absence of real life-or-death consequences keeps the lid on dangers that might blow out our attention.

Gilmore evokes a unique form of nostalgia at this moment. The show was never much of a ratings smash, but it did very well for the second-tier broadcast network the WB (for the show’s last season, the WB reshuffled into the CW). That means most of us weren’t watching it weekly on its first run.

That being said, Gilmore was sent into syndication in 2004, after its third season. And so it became part of the general background noise of daytime and early evening TV in the nearly two decades since.

Gilmore’s mixture of nostalgic familiarity pairs nicely with its season long (and longer) arcs, which most viewers have never examined. So there is this strange feeling when watching the show — it has the comfort of nostalgia with the shimmering newness of something you’ve never seen.

And beyond that strange pairing, the nostalgia it deals in is the latest kind: nostalgia for the naughties.

Ending a relatively brief ten years ago, the naughties are unmined nostalgic territory and are still a ways off from the much upheld 30 year nostalgia cycle. That means Gilmore doesn’t lay in that fatigued pile of the over-sampled, over-referenced pop culture group of the current nostalgia trend (today it seems to be sliding from the eighties to the nineties).

The nostalgia doesn’t end there. As a show focused on the milestones of childhood and parenting, the content is built out of the things everyone can find something to be nostalgic about. To go one step further, the show is set in the sleepy New England town Stars Hollow. Stars Hollow sprouted from the mind of show creator Amy Sherman-Palladino when she visited a similarly sleepy Connecticut town and experienced such overwhelming nostalgia that she pitched the show entirely on the setting. This show is an onion of nostalgic layers, and that onion-like quality is the only reason it makes me cry.

Gilmore is notable for the cracking wise protagonists who chatter incessantly in bubbly repartee in a whimsical small town filled with other clever talking, unbelievably good looking people. At its worst, the characters appear like narcissists who are psychopathically entertaining themselves by running spontaneous monologues. But that is at its worst. For the most part, it hums along with relative ease — just enough references and kind-of-funny-jokes to keep your ears leaning in.

Much like the level of stakes mentioned earlier, dialogue that is frequently hilarious and razor sharp would not be bingeable. It would be satiating. Great TV rides the line between fulfilling and vapid, compelling and boring. It’s middle seat viewing: you’re not laid back as you fall asleep or sitting on the edge. Neither is sustainable.

So it must be noted here, this is not an insult to the show. I’m not saying that it isn’t as smart or funny as the writers think it is. I’m saying that the writers were working on a television show, and that requires a certain kind of writing.

As I continue to watch copious amounts of Gilmore, I ask myself what it is I’m consuming. Why is it so comforting, especially now when in lockdown?

Of course, a major component is the simulation of social connection, of living a life. Without the regular activities that define us, we sit at home drowning in an ego that has nothing to boost it, comfort it, confirm it. It is a feeling of coming apart. While yogis and gurus have long taught us to transcend the ego, no one said that we should dive into the practice of its annihilation without any warning or preparation.

And so, we need to do something to give us a feeling of social reality.

But that only explains viewing in quarantine. What begins to open up in us is the horror of all the viewing we did before we were confined to our houses. Before the lockdowns, we were already sinking into confinement. We were already feeling the need to reach out to comforting media. Think about it: even when we were free to travel and cavort and socialize in large groups, we were already binging television shows.

In that way, Gilmore is not only a view into the needs of our current life in these extreme circumstances — it is a view into what needs we weren’t fulfilling before.

While other forms of escapist media involve danger, excitement, explosions, violence, and other kinds of far out living, Gilmore provides something else. It provides a cozy experience where turbulence, for the most part, comes in the form of everyday inconvenience and miscommunication. It shows us the dream of a life of general comfort, living in a community we know and love and that knows and loves us, being in a perfect relationship with our child or mother — it’s the idyll of being nice people living nice lives.

The enduring popularity of Gilmore is evidence that these humble fantasies are unrealized in us. That we binged this content even before quarantine points to a profound lack of nurturing in our society. We watch Gilmore because we don’t live in Stars Hollow, because we don’t connect fully to our family, because we don’t know the nice life. The question transforms from asking what comfort Gilmore Girls gives us, to why we need its comfort in the first place.

From Benjamin Christenson’s Häxan (1922)

The pursuit of understanding the world always turns toward mysteries. But the pursuit of beauty acts as balm for this desire to know. In beauty, the mystery is not pursued in order to break it, it is pursued in order to behold it. Beauty, then, does not try to destroy the mystery to find the truth inside, rather it accepts the mystery itself as the truth. Do not try to solve the riddle, whisper its words and cherish the sounds.

From Benjamin Christenson’s Häxan (1922)

Horror utilizes archetype and symbol more than perhaps any other genre. Its stories are ones of fear, and fear, above all other emotions, is precoded by the collective unconscious. We arrive on this earth with vivid fears. Fears of fanged creatures, of howling in the night, of mist, of spiders, of the dead, of darkness.

We then continue to manufacture new fears out of the stuff of our lives: the traumas we experience and the traumas we witness. Our fears begin with an inheritance and always accrue with the product of our own hard work. But even these fears often maintain direct lines to more ancient predecessors. This is because the traumas that serve as the raw materials to our new fears are only traumas if they realize a fear already there.

And so provoking fear requires the recollection of an archetype already feared. The archetypes are productive inserts for storytelling, borrowed from our shared patterns of fear.

Plato’s world of ideal forms is a world without articles. You don’t come upon a dog, you come upon Dog. You don’t go to a theater, you go to Theater. There are no specifics, only symbols channeling power through a refraction shaped out of the bends and folds that make up the ideal form. These forms are made out of the same mental stuff, bent into their unique shapes — perhaps fear works like this, too.

Our nightmares are the closest guides to thinking this through. How we conjure up the strangest stories leading a path of anxiety to panic to complete and total fright. In the morning, we sometimes wake to find the events of a nightmare certainly strange, but our response is incongruous. A friend of mine recently recounted a recurring dream he had as a child. In the dream, he rises from his bed and goes to the window to see a deer and a dog looking in at him from beyond the glass, their black eyes gleaming. What an interesting response to this image, fear. And yet, the terror always accompanied the dream with each return. The fear itself tells us something of how to read the message of the dream. The stirring beasts beyond the room in the night. Beasts that also stir within us. That call us to some other nature outside of walls and beds and language. The image does not seem frightening to the waking mind, but the image connects the dreamer to the realm of fear, like a key to a forbidden room or a trap door to the undiscovered basement. The fear itself teaches the dreamer that an archetype of fear is speaking.

But a work of horror cannot bring emotion to inform the text. Rather, the text must draw out the emotion. And so, horror cannot add to fear before establishing it. Horror thus calls into being images of an archetype of fear, and can only augment or modify once the link is established.

From Benjamin Christenson’s Häxan (1922)

Horror is an aesthetic pursuit. A work of storytelling. Being an aesthetic pursuit, horror operates around its own conception of beauty — here beauty simply means an aesthetic ordering that is appreciated, be it through paralyzing terror, erotic arousal, gentle gratitude, or any number of states of appreciation. [1] As we have discussed, horror creates this beauty by weaving archetypes of fear throughout the other elements of the text.

Horror trades in the least touched truths, everything that is refused to be true and yet endures. When we sink our fears below the surface of our thoughts, some die, proving to be temporary phantoms of anxiety and paranoia, trifles that come and go. But not all of these fearful thoughts pass forever. Those that do not drown under the water of our unconscious float to the surface again and again, never leaving, never dying. Horror is made up of the things that survive the drowning.

And so any philosophy of horror must hold this position: take account of the unbearable truths, see what you blind yourself to. What unites all horror is that it attempts this one act, returning these dark truths to us.

Horror is the unsettling rise of known and unknown truths from the dungeons where we keep them. Horror is a philosophy, a metaphysics, a spiritual path that speaks to us about the things we struggle to forget. It is therefore a rigorous path, requiring intellectual courage and spiritual bravery. It is the handling of that which must not be handled. Horror reminds us of that which we collectively agree we do not wish to be reminded of.

This path is all encompassing, because the unrefused truths are not disqualified from it, it is the insistence that both refused and unrefused are held together. These truths are brought together in the vessels of their archetypes. The tension arising from that gathering is the magic of horror.

From Benjamin Christenson’s Häxan (1922)

[1] Not unlike Nehemas’ conception of beauty as a representation of a lack, only because a lack is also pursued.

William Blake’s Newton (1795)

I’m a big believer in the New Year’s Resolution, the art and craft of creating, tracking, and pursuing goals. So as I went over my resolutions for 2020, I spent a lot of time on YouTube watching self-help gurus explain the path to self-mastery.

Dopamine detox, intermittent fasting, time boxing, neurochemical hacking, morning pages, routines of the masters, olympic weight lifting schedules, speed reading techniques, daily meditation and mindfulness, etc. etc.

Through all the confessionals, bullet points, trademarked systems, and personality platforms, one thing holds across it all. There is a persistent internalization of an ideology. To be fair, it is the reigning, defending, undisputed ideology of our time: individualism.

William Blake’s Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils (1826)

Let us take for our first example a consistent platitude of the self-help universe. It is at the same time meant to shame and call to action. It focuses the reader/viewer/listener on their life as it is and masterfully contrasts it with the dreams unrealized, the life unlived.

You choose what to do with your life.

To a certain degree this is true. You are choosing to read this post right now (thank you, by the way). Similarly, when you sit in bed and scroll through Instagram for a half hour before bed, you are choosing to do that with your time. What’s supposed to go through the mind of the reader/viewer/listener are images of climbing mountains, travelling to Italy, building a business. It’s supposed to make you feel like, starting now, you can change your life.

But that isn’t really true.

The self-help space is dominated by a fiction: you are an individual. But you aren’t. You are a node embedded in a network of many other nodes. You are bound by social influences. You are not working the job you want. You are working a job that was available to you, that you must work at to survive. Someone has to do it. That someone is you. You speak a language you were taught or that you learned through necessity. Your entire universe is built out of concepts and historical legacies completely out of your control (it’s out of anyone’s control, which is both encouraging and somehow also unspeakably terrifying).

There are choices you can make, but you are not the sole decider, in many cases not even the primary decider. Your life is built inside of concentric circles of communities. These collective realities circumscribe everything you can ever be, so much so that it is doubtful you can even imagine a state of being outside of these constraints — which helps, as a prison is much nicer when you can’t see the bars.

But self-help can never broach this topic because the entire racket runs on the illusion that your dissatisfaction in life is a result of (to some determining degree) your personal choices. Thus, if you change your choices, you can change your life. But the self-help racket goes even further. It doesn’t just propose that your choices can change your life. It also claims that if you make some set of specific choices, you can reliably conjure the life you want. And what are those specific choices? Why, the ones hiding behind the paywall of course.

That last bit, about the paywall, is the traditional model. With the rise of free content delivered through sponcon and Patreon accounts, an even more perverse model has arisen. Communities of eager strivers now gather around gurus and pay money to support the guru, the discussions around whom focus on how this content has helped the lives of the strivers. These strivers, however, never seem to “solve” their life. They continue to support the guru and consume their content, sure that at some point it will all click. They see other strivers post glowing reviews, and so this striver is assured they will experience these breakthroughs themselves. In the meantime they send money and write their own gushing reports of self-transformation — the only kind allowed in such a community of strivers. Optimism! Optimism! Optimism! The ferocity of these strivers belies, at least to the Freud reading dinosaurs among us, a deep insecurity about the whole thing. So why do they continue their striving? Their monthly tributes? Because their lives are so miserable that this project of turning it around must work. So they white knuckle it. When they see their own suspicions of the program written by others, it must be stamped out. It is the interior battle exteriorized.

It is for this reason I suspect that at this point, no one embedded in the self-help universe is still reading. And so, knowing that only the nihilists are among us, let us speak freely.

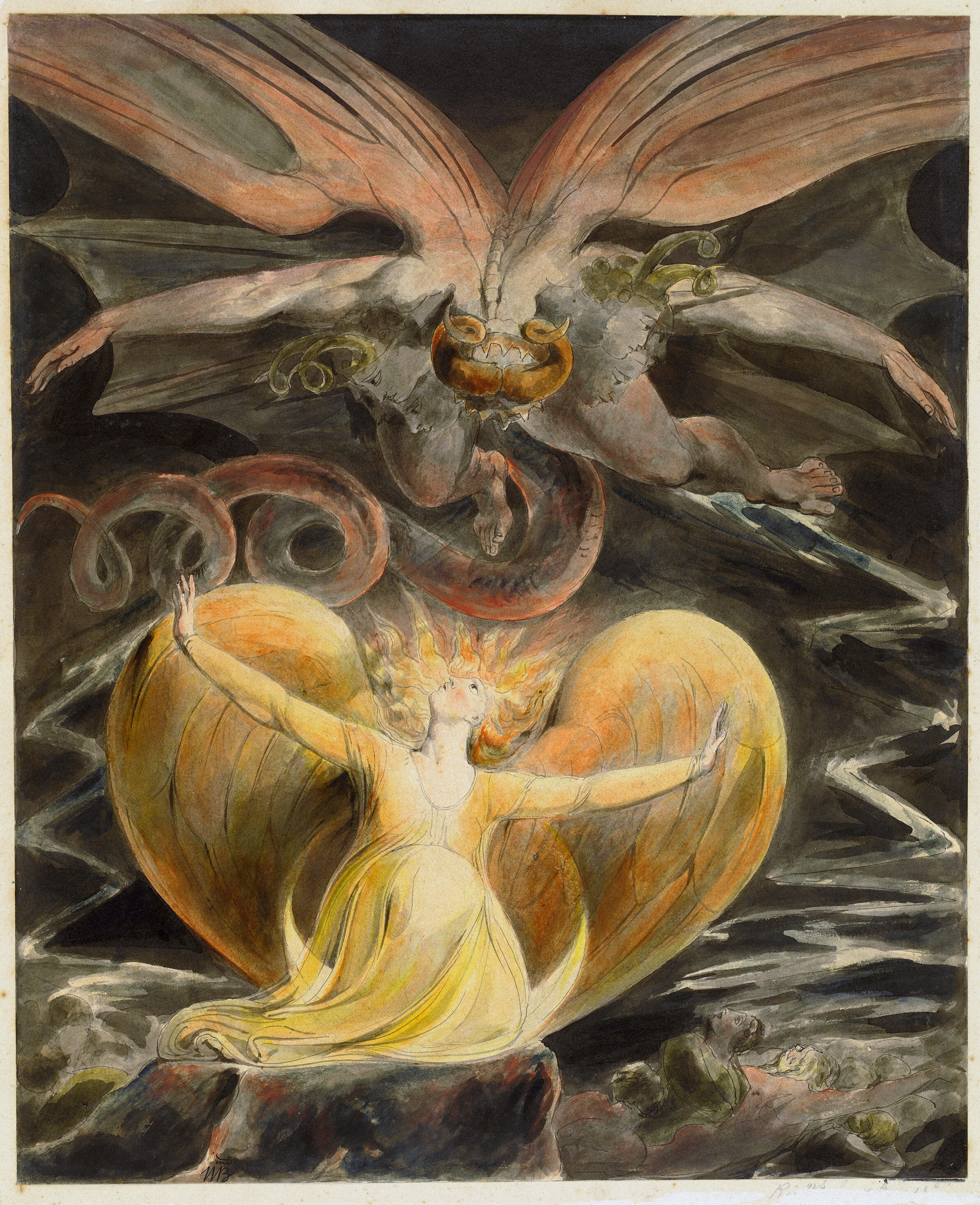

William Blake’s The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with Sun (1805)

It is not true to say that you can’t do anything to improve your own life. That is the cultish commitment of the nihilist, the person who has lost too many times to allow themselves to believe in hope.

But, to reiterate, you can change your life. You can quit drinking, helping you wake up happier, better rested, and with fewer apologies to text out while sitting on the toilet for an hour spraying lava into the sewage system. You can read more, educating and entertaining yourself in a way that detaches you from the dopamine zapping, self-esteem shredding hamster wheel of the social media scroll. You can workout and eat healthy, increasing your energy, lifespan, and sex appeal.

Even so, no guru will tell you something you don’t already know about achieving these goals. Yes, you want to get sober, you want to read more and scroll less, you want to get healthier. Yes, you know how to do these things, more or less, and if you don’t already, you are a few bullet-point lists away from knowing the bulk of what there is we know about accomplishing it. And yet, it never happens, at least not permanently. Maybe for a month. Maybe for a year. But after that? You quit drinking and notice your mind is clearer, your belly is slimmer, your wallet is fatter, and your relationships are stronger — but what trips across the mind from time to time? What whispers to you in the midst of work stress or after a fight with your spouse? Drink. And eventually, you do. And when you do, then comes the return of all the problems. And if you don’t? What do you notice? Yes, things are better, but things still aren’t good. If things were going so great all the time, that little word wouldn’t come across the transom.

That is the problem with eliminating problems: they reveal there is no end, that the problem eliminated masked an unending line of problems. Health freaks who hit their goal weight wouldn’t “choose” to go back to their previous state, but they still feel dissatisfaction with life. It is the person who never stops feeling fat who keeps eating salad and showing up for spin class — but that requires still feeling fat. That’s because the problem wasn’t being fat, overeating was a symptom. “Feeling fat” is a socially taught shame that they could use to label that feeling that life isn’t quite what they’d hoped for, that they aren’t as happy as they want to be.

A personal example: I quit smoking for four years. My lung capacity improved. My skin improved. I didn’t reek of tobacco smoke. I saved tons of money. But do you know what never improved? The actual happiness level of my life. I didn’t want to return to the bad parts of smoking, but when I eliminated the bad parts of smoking I never scraped the surface of the real machinery of happiness.

So how do you become happier?

William Blake’s Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing (1786)

Well, I’m going to share the secret with you right now. And the secret is…

You can’t.

You can’t become happier. You can live a more meaningful life. You can quit all your bad habits. You can reach goals. You can go to bed with more partners. You can lose weight and build muscle. You can cut out on needless expenses. You can build a perfect morning routine. You can work through past trauma. And all of this will make your life better than it is now. But you can not become happier.

That’s what makes self-help a scam, whether the purveyor knows they are running a scam or not. There is simply no way to marshal motivation, discipline, and popified cognitive behavioral therapy to become happier. If there was, we’d all know about it. There’d be happy people walking around who used to be miserable who also didn’t seem like they were recently addicted to a new drug or locked in the performative joy indicative of cult membership (though, on second thought, maybe drugs and cults are the secret to eternal happiness).

There is good evidence to suggest that major life events, both negative and positive, don’t adjust happiness long term (although it appears trauma might be able to negatively affect happiness long term). But this unchanging happiness state is what we can all observe in our own lives. We have all had major events in life and find that, sooner or later, we return to our home position, more or less.

But there is good news, and it relates to something we talked about earlier. The good news is that your personal, individual happiness is not that important. In the end, the world does not really need you to be happier than you are. And, in a way, that makes it okay to be a person who isn’t very happy. For one, it means you are already there where you’re going to be. You are already achieving the full happiness potential you have. Don’t worry so much about it — there’s no need.

So what do you do with all that desire to act, to break free from the chains of your life? You can call a friend you haven’t talked to in a long time. You can join social and political organizations to help others. You can take your dog on more walks. In other words, you can stop acting like your happiness is the most important thing in the world.

And when you aren’t focused on how well you are feeling, feeling bad doesn’t matter quite as much.

William Blake’s Frontispiece to the Song of Los (1795)

Vanderpump Rules is an institution of reality television. It’s a spin-off of another reality television institution: The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills. The show focuses on the front-of-house staff at an upscale restaurant in West Hollywood called SUR (which stands for, I shit you not, Sexy Unique Restaurant), owned by a gorgeous Brit who acts as benevolent dictator, wise counsel, and momma bear for the characters of the show.

The cast is a group of 20 and 30 somethings who all moved to LA in the pursuit of fame. Throughout the seven seasons of the show, they try their hands at modeling, acting, and singing — whatever might make them famous. They believe they can do it because of their looks. And in a way, they did do it, but by being on a reality show about people who are pursuing fame. (This creates an odd web of psychoanalytic confusion that we won’t be delving into, but somebody should write a book about.) What they find themselves locked in, through circumstance and presentation, is an all too familiar format of “real” continual conflict.

In other words, Vanderpump Rules is professional wrestling. [1]

After binge watching every season of Vanderpump, I noticed a striking similarity in the storytelling between it and professional wrestling. In professional wrestling, characters are ordinally aligned based on card position, while laterally aligned based on character (heel and babyface: bad guy and good guy, respectively). Matches are given meaning (or heat) through ongoing interpersonal conflicts (or feuds). Stakes are raised because, as with legitimate fighting sports, there are championship title belts to win and, as with real life, pride is on the line.

Thus, a title match between a heel and a babyface that comes at the end of a long, personal feud will have a greater amount of heat than a match between two babyfaces with no feud and no belt for grabs (that is how things should typically work, never underestimate the power of bad writing to kill fan interest in what should, on paper, be a highly anticipated match). On the other side of matches and, more importantly, feuds is the rise and fall of wrestlers on the card. While it is not always the case that coming out on top of a feud with a bigger star will catapult you to their level or above, it is almost always the case that such a course will have to take place to send you there. Necessary but not sufficient.

Wrestling is able to generate drama with a slowly shifting cast for years and decades on end because the constraint of a sports promotion creates easily understandable characters, conflict, and stakes. To some degree, it writes itself.

Vanderpump functions in almost precisely the same way. Card position is essentially screen time and sphere of social control within the friend group. Heels and babyfaces are clearly defined through presentation and editing, and these definitions can change (as in wrestling) as certain events will cause characters to turn (move from one to the other). Once a character turns heel, by cheating on their girlfriend with a bottle service waitress in Vegas for example, they will be framed in a different light by the producers, and the candid confidential intercuts will show other characters scoffing at the new heel’s deeds. Characters will often feud as well, leading to weeks of conflict, forcing others to take sides and shun/embrace accordingly. And, as in wrestling, Vanderpump has a setting and conceit that naturally breeds drama: the front-of-house at a restaurant entirely staffed by young, attractive people hungry for fame.

To see how this works, let’s look at the central feud of season 1 of Vanderpump Rules. Scheana is introduced as the new waitress at SUR. The only thing current reigning champion Stassi knows about her is that she was the mistress of a married man tangentially related to the main cast. Stassi is in a rocky relationship with the permanently horny Jax, and so her confidence is low and her jealousy is high.

Stassi induces her allies (namely, Katie and Kristen) to turn their backs on Scheana. In response, Scheana begins to provoke Stassi further — one such incident: she applies sunscreen to Jax’s naked upper body, knowing that Stassi and her clique are watching from a distance. This feud developed Scheana as an outsider who is threatening to Stassi’s reign. As the opening season, it also helped describe the group dynamics at SUR. Jax is promiscuous and untrustworthy. Stassi is jealous and dominant. Katie is a quiet, loyal follower of Stassi. Kristen is a loud, emotionally unstable, though still (mostly) loyal follower of Stassi. By the end of the season, Scheana finally reaches out to Stassi after it was revealed that Jax had cheated on her with a woman in Vegas (Stassi’s friends had insisted this was just a rumor until Jax admitted it). This revelation created a rift between Stassi and her followers. Scheana’s embrace of Stassi showed us a new side of Scheana, turning her face. Consequently, Stassi’s loss of her social power base destabilized her regime, dropping her down in status.

As we can see, Vanderpump has incredible similarities to professional wrestling storytelling. Feuds help define and shift loyalties, with the outcomes shifting order on the card. The conceit of the show produces a “drama box” which achieves a unity of opposites (a force that compels the antagonists and protagonists to continue engaging with each other). Stakes are easy to recognize and add weight to the events and the outcome through more or less universally understood motivations.

There are differences as well, of course. In wrestling, all interpersonal conflict is settled in an officiated bout of physical violence, and all roles are clearly defined through a sports analogy. In Vanderpump conflict is settled through manipulation, rumor spreading, and finally squashing the beef through new terms of friendship, and all roles are defined through friend group hierarchy. This difference points, however, to another similarity. Both forms are highly gendered to the toxic subspecies. A chair shot to the head of a rival is a fairly obvious form of toxic masculinity, just as using physical intimacy with a rival’s partner to make your rival jealous is a form of toxic femininity. Both forms are coded in the gender stereotypes of the same culture. Wrestling is Vanderpump for boys; Vanderpump is wrestling for girls. (Don’t yell at me, we all can see the bad gender politics at play.)

You might be saying to yourself that while, yes, both reality TV and professional wrestling share certain dramatic contrivances and narrative tropes, the same could be said for any long running sequential storytelling — from soap operas (the most commonly compared media with professional wrestling) to comic books. But the most important feature that Vanderpump and professional wrestling share is this: the insistence of reality in the presentation.

Kayfabe is professional wrestling speak for the canon-world. In kayfabe, what goes on between the ropes is a legitimate sporting contest. What is caught on camera behind the scenes is video footage of true events. Ric Flair is a philandering party boy (this one is actually true). The Undertaker is a man risen from the dead to do battle in the squared circle (this one is likely not true). While kayfabe used to be protected at great lengths (some members of the industry even going so far as to perjure themselves in court to “protect the business”), the last three decades have seen the complete unveiling of the business — i.e. that (I hope you’re sitting down) wrestling isn’t real. That being said, there is still a deep protection of the suspension of disbelief during the show. Wrestling television does not list writer credits at the end of its broadcasts, and at the end of a wrestling show, wrestlers do not step out arm-in-arm with their in-character enemies to bow for applause. (Well, not usually.)

Reality TV has not yet been completely unveiled as an artifice. Despite the clearly scripted nature of events, impossible-to-film situations, and revealing editing gaffes, viewers of reality TV are by and large willing to convince themselves that what they are seeing is filmed reality. Yes, you can find a number of articles that expose reality TV as a form of fictional storytelling, but the audience is still holding onto some shred of hope that it’s mostly true. This is reminiscent of wrestling fans in the 70’s, who would often say things like, “Some of that stuff is fake, but this match is real.” Despite the bad acting and worse writing, viewers of reality TV can still buy into the kayfabe.

Something happens inside the alchemy of a presentation that pretends to be real that does not happen otherwise. Now, most television shows do not break the fourth wall, but the presentation is coded as a written, directed, and acted presentation. When the presentation is coded as a documentary or live sporting event, we get a form of storytelling that seems to be filling a similar role. But what role is it exactly?

Why do we love these forms of storytelling? Because they are gendered in the extreme, they act as both release valves and information receptacles for learning how to perform our genders. Because this form is tacky and low brow, we protect ourselves from over-relating. And because this form is supposedly “real”, we read it as closer to how the world works than other forms.

The social expectations of males are so obvious and up front in wrestling that fans both play through their fantasies of violence and glory while not identifying so much that they become violent and vainglorious. Wrestling exists in a realm so distant from their own lives that there is no fear of learning too well and becoming untenably abusive people. On the other hand, wrestling also gives its fans lessons in the expectations of masculine worlds (expectations that are often coded and never explicitly laid out in the real world, creating a challenge for mastering them). It is through wrestling’s simplified dramatic artifice that fans can distance themselves from the idea that they are confused as to their own masculinity. But among the larger than life characters and the instant feedback of the crowd, they learn about the male world.

Vanderpump works the same way, although here it is flipped to the gendered realm of the feminine. Here we see interpersonal confrontations and disagreements based on the most tenuous grounds and paranoid suspicions — feelings and intuitions we all have from time to time, but that most of us are trained to ignore, redirect, or suppress (deep, deep down). When the characters act on these impulses we forbid ourselves to act on, the private reactions of others in the social group are interspliced moment by moment, providing live social feedback. By watching Vanderpump we can live out the impulses with devilish joy while getting a read on how people would perceive it if we did. And we can simulate it without ever facing consequences (Stassi said it, not me) or fearing that we will succumb to them in our own lives. The setting and presentation are far enough from our experiences to distance us from repeating that behavior, though similar enough to translate.

Both formats inform our gender performance and provide release valves. There are conflicts in everyday life where you might like an open licence to commit violence against your boss or to spread destructive rumors about the person dating your ex. As adults, we know that we should not do these things, but we can’t help wanting to do these things.

That release valve is precisely why wrestling and reality dramas are so dangerous to the middle brow mind. They are considered low brow because the characters in them are uncultured, dramatic, highly reactive people. Their behavior just would not do at the country club. They represent all of the drives and impulses suppressed by the WASP, middle class culture that turns its nose up so high on approach. Middle class repression dismisses these forms because it is so afraid of the drives and impulses they depict and even celebrate.

When we enjoy trash TV, we are enjoying the undeniable, ever present features of human psychology that bourgeois values shun. Trash TV is necessarily working class culture. That is not to say that all working class people enjoy it and all middle class people loathe it, but rather these highly charged reactions are driven by class dynamics and class experience.

To top it all off, enjoying these forms requires admitting to some level of credulity. Critics will point to pro wrestling or Vanderpump and exclaim, “You think this is real?” So nervous are they to be considered duped by trash TV, that they have to insist that enjoying it requires buying into the kayfabe, making sure no one believes the same is true for the middle class critic. In fact, these are easily enjoyable forms even (and in some cases especially) if you know they are fictional presentations. But again, the middle class anxiety around appearances can not bear to be mistaken for believing these programs are real.

Thus, there is a kind of reverse-class gate keeping going on. These are cultural spaces structurally made to repulse (and so exclude) anyone with the middle class attitude. It is the popular made exclusive for the populous. It is the mass keeping out the few. And above all: it’s really fucking entertaining.

[1] Yes, I am aware that WWE produces reality TV shows starring female members of its locker room. These shows cater to a female audience and are broadcast on networks grasping at the female demographic. I am using Vanderpump Rules for comparison because: (A) it isn’t produced by a wrestling organization and so the similarities are less expected, and (B) Vanderpump Rules is an incredible show that I would much rather talk about than Total Divas or Total Bellas.

Barnett Newman’s Abstract (1961)

We were at a BBQ out on a friend’s farm, sitting on the porch surrounded by half-empty Miller Lite tall boys in the early night. I offered a new acquaintance some of my kratom. They declined with a slight frown, saying, “No thank you, I have an addictive personality.”

I’ve heard that phrase many times in my life, always someone self identifying with it. Once said, it comes heavy laden with assumptions. Images of long nights in years gone by, struggling to free oneself from the clutches of this or that bad habit. Alcohol, cigarettes, pornography, cocaine, binge-watching Netflix, coffee enemas, Candy Crush, whatever it might be — this person has seen inside themselves as through a glass darkly. And after one (or many) dark night(s) of the soul, they emerged with a hard earned truth of themselves that they carry as a sword and shield against temptation.

“I have an addictive personality.”

What that means, whenever you hear someone say it, is rather up to the speaker. It is a medicalized term, borrowed no doubt from someone else equally unqualified to diagnose as the speaker is. Are some people more likely to become addicted? Maybe. Does becoming addicted make you more susceptible to become addicted to another substance? Maybe. Is there even a coherent enough shared understanding of what addiction is to go around labeling behaviors as addictive according to a checklist? Maybe.

But in each case, of course, maybe not.

Barnett Newman’s Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue IV (1969-1970)

So I’ve turned to analyze myself, not to see whether I have an addictive personality but to suss out why I hate the phrase itself. I am not angry so much at self diagnosis per se. After all, any trip through the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or to a psychiatrist’s office teaches even the most obtuse observer that diagnosing mental illness is not an incredibly certain sphere. As long as the appearance of symptoms are generally maladaptive (i.e. they get in the way of living a full and productive life, whatever that could mean — maybe just living your best life or simply doing you) and you check enough boxes under an illness heading, you have that mental illness.

There is no brain scan to determine if you either: A) tend to be a homebody during the winter, or B) are afflicted with seasonal affective disorder. There isn’t even a clear idea of how such a scan could possibly function. [1] Scarier still, some mental illnesses could plausibly be diagnosed in two people who share few if any symptoms. This leads to the sensitive-guy wisdom that “No two depressions look the same,” which is dispensed with knowing empathy and yet should create a shuddering chill. If two depressions can be so different, why would we consider them the same thing?

Dogged defenders of the DSM will point out that a multi-form mental illness like depression has specifiers to classify and subclassify, to whittle down to a much more specific diagnosis.

Others will point to experiences in their life with people suffering mental illness and recall how you can clearly tell that something is off. And that is true with some mental illnesses that express themselves with extreme behaviors that are more or less the same across the entire diagnosed population.

So I highlight those countering points for two reasons. For one, they happen to be true and point to the fact that the medicalized approach to mental illness is reaching at something — there is a there there. For two, if I don’t bring them up, I can’t neatly clip those points out of the discussion for my own intellectual convenience. I’m not here to complain about any and all medicalization of mental illness as if all psychiatry is a scam diverting us from going clear and reaching full OT. What I want to highlight is that the medicalisation of mental health has trickled into the general population and lends scientific wording to a potentially poisonous way of being. Not only that, but the trust people give to scientific claims passes over the bridge of this borrowed wording and nestles inside concepts that lead people to trap themselves in self delusions.

Deep breath.

To put the problem simply: when we borrow wording from science to describe our self-conception without the rigor of good science, we can end up trusting these self-conceptions with the same trust we place in good science. To put the stakes simply: our self-conceptions are often damaging, and it is difficult to overcome a self-conception (even a clearly damaging one) when we believe it to be rooted in hard, scientific Truth™. [2]

Barnett Newman’s Adam (1951-2)

When someone thinks about themselves as an addict, they typically think in terms of the “alcoholic” inside Alcoholics Anonymous jargon. Namely: once an addict, always an addict. If it keeps someone from ever smoking another cigarette and falling back into a pack-a-day habit after years of abstinence, fine. But it happens to not always be true. Much, much more importantly, this attribution of a fixed diagnosis to a not-necessarily-fixed psychological tendency is paradigmatic of the lay discussion on mental illness. The equation (where a scientific sounding label equals an inescapable truth of who a person is and could ever be because science says so) at some point leaked out into the self-conception of so many of our psychological experiences.

How many people in your life have self diagnosed social anxiety? Why is that so bad? Because once someone “has” social anxiety, it is a feature of how they function and an inescapable one at that.

There is a parallel line of thinking in our culture where we are expected (rightly, in most cases) to be understanding and considerate of neuro-divergence. While well intentioned, the introduction of this belief stirred into the medicalisation of our own self-conceptions creates the real witches brew. A self diagnosis is not only a way to set proper expectations of yourself but also a claim for special consideration on behalf of the community. The social group is now responsible for managing any personality trait or habit that you have self diagnosed as mental illness — regardless of the validity of your self diagnosis.

It’s time to compare two examples.

Someone notices that they have trouble making new friends after college. In the years after school, their reduced socializing led to nervousness when interacting with new people. This person might then decide to do something about this, to solve their problem because it is their problem. They swallow hard and step into the line of fire and withstand the anxiety of social interaction with new people until they learn how to make friends as an adult.

But if someone in the same situation decides that they have developed social anxiety disorder, then the issue of dealing with these feelings transforms from a personal responsibility to a social one. “You have to put up with my social anxiety and create spaces where I can interact and/or benefit at the same level as those without it,” says so much of the contemporary discourse. The person with social anxiety disorder can not be expected to easily and openly interact with new people, nor are they expected to change this feature of themselves.

To a certain degree, of course we should make efforts to craft social spaces that are welcoming to all people. We should aspire to make all people feel comfortable and to take them as they come, and we can change the way things are done to be more inclusive of the neuro-atypical whenever we can. That being said, we are all of us variants from the “typical”, lacking in certain life skills. In some, these variations are in the extreme. And it is hard to see how we can optimize social spaces for all people without reducing the benefit of the spaces for the vast majority.

If we want to take part in the social realm (not just for socializing but also participating in public life) then we have to, as much as we can, adjust ourselves to fit the social. The nature of the social realm is that it is not personalized. Demanding a personalized experience of the social is not possible for all people because the social has to take into account so many different human needs, many of them contradicting across individuals. And so, while the social realm should make an effort to be inclusive, likewise individuals should make an effort to fit into the social realm. That the fits are not always perfect is sub-optimal but unavoidable.

Barnett Newman’s First Station (1958)

It is not the responsibility of the social realm to be a good fit for any single individual, but by framing certain unpleasant features of your inner life in a pseudo-scientific medical diagnosis, then demands for special treatment can be made on the wildly prevalent grounds of identity politics around neuro-divergence. So micro-group visibility and acceptance and access is then weaponized around personality traits that are, in many cases, fixable through personal action.

When such a critique is given, many will protest that it is easy for people without mental illness X to dismiss the experiences of people with mental illness X. Almost anyone can see their point. If you don’t struggle with something everyday, then you probably have difficulty understanding the scope of its impact and the contours of dealing with it. And the phrase “It’s all in your head,” is cold comfort and inappropriate. But this argument, while obviously true so far as it goes, is pushed against any unevenness whatsoever based on self-reported symptoms. This puts the entirety of the burden on the social realm rather than on the individual. In some cases this is justified, but how do we determine which self diagnoses are legitimate and which are traits that could be fixed by taking personal responsibility over resolving them? The current discourse protects both cases.

That renders the responsibility a deeply personal one because you are the only one with access to the experiences of your own mental health (in most cases). So the culture must insist: the individual has responsibility to fit into the social realm. The burden to integrate and participate in the social realm is on the individual in the last instance. [3]

Barnett Newman’s Concord (1949)

“I have an addictive personality,” is not, in my experience, as undermining of social life as its self diagnosing cousins, but it does share a root system. If thinking of your personality as “addictive” helps steer you clear of destructive behavior, it is probably best to stick with the phrase, no matter who it irks at the BBQ — even if it irks the guy who is going to go home and write an essay about how this kind of thinking is destroying the fabric of collective human enterprise and the possibility of world-historic transformation of society.

In that sense, the negative reaction I feel when I hear that phrase is really just a symptom of my own pathological pretentiousness. But that kind of makes you think. Though this is not accepted in the DSM (yet), it is a form of neuro-divergence and should be respected. It is all too easy to wave away my symptoms if you don’t experience pathological pretentiousness — must be nice. If you find yourself at a social gathering with someone who suffers from pathological pretentiousness (especially of the contrarian subtype) it is very inconsiderate to go around saying things like “I have an addictive personality,” based solely on the fact that you can’t go a single morning without your cup of coffee and you played too many video games in freshman year to the detriment of your GPA.

I digress.

The solution to this problem is fundamentally too personal to find a clear path. On the one hand, neuro-divergence should be respected and handled with empathy and a great deal of listening, and social spaces should be as welcoming as possible. On the other, this creates a moral hazard where people can self diagnose their way into special treatment that hollows out the collective element of social life and puts undue pressure on the social realm to cater to individual needs at the expense of group needs. How do we insist on the importance of one side of the scale without neglecting the other?

I suppose we can borrow the rule of thumb used in the diagnosis of mental illness: are the symptoms maladaptive?

Barnett Newman’s Onement I (1948)

[1] The reader will shout at the screen that the difference is: how do the symptoms affect your life. But feeling like staying at home can affect your life negatively without being some inescapable disorder with no solution. This thread of treatability is picked up later on in the essay.

[2] We will set aside for now the incredibly interesting tangent of why and how we place our trust in science, as this is a topic already well-tread in critical theory. Needless to say, I’m making no value claim on trusting science as a discourse one way or the other but simply noting that we do, as a culture, place trust in science — or at least sciencey sounding claims.

[3] Now that liberal activists and left-liberal activists have so thoroughly taken up identity politics as the primary vector of social action, the entire purpose of changing the social realm to meet the specific needs of a micro-group becomes centered as the entire struggle itself. The social realm must integrate and eliminate all unevenness of entry for a particular micro-group so that said group can participate in… eliminating unevenness of entry for itself. We now have a snake making dinner of its tail — which is probably a self diagnosable disorder.

In the absence of a class revolution as the primary goal, the majority of US leftists (who long ago replaced class with identity as the revolutionary subject) serve only this ouroboros. Centering class as the primary political battle line is derided by identity politics as class reductionism. The thinking goes that if you are talking about class, you aren’t talking about sex — which makes you sexist. You are not talking about race — which makes you racist. And so on.

Identity politics thereby makes class the only lens through which politics are not able to be defined. By this fancy alchemy, class conflict is impossible, because no forward movement is allowed until every single person, no exceptions, is in on the game. No identitarian struggles are to be left unstruggled before any steps may be taken toward broad, collective interests (i.e. class interests).

The Devil Wears Prada (Dir. David Frankel) is a 2006 comedy/drama of some note. In the world of (the unfortunately named) “chick flick” genre, it stands as a major achievement of the oughties. It is remembered for its defense of fashion culture, Meryl Streep’s performance as a coolly sociopathic magazine mogul, and the archetypal struggle between generations, mothers and daughter, values, and class.

The film should also be recognized for its non-self-congratulatory escape of most chick-flick tropes. It passes the Bechdel test with flying colors and in fact fails the reverse Bechdel (there are no scenes with more than one speaking male character — ever). It is a female dominated movie about a traditionally female world, and thus it is able to side step the patting-yourself-on-the-back-for-having-a-strong-female-character that was prevalent for the second half of the last decade and follows us up to this present day. In a similar vein, it is a film about women where they aren’t shoehorned into acting “masculine” in order to be respected.

But these aren’t the reasons we’ll be diving into the film today, though they are perhaps reasons why the film should be analyzed further. What concerns us here is a major emotional feature of the film: the experience of rising in social class as an intoxicating experience and its connections to the female in our culture.

Hello, it’s the future calling, they want their Bechdel-test-passing script back.

When the film begins, Andy Sachs (Anne Hathaway) is a recent journalism grad who, after diligently chasing down any and all job openings in New York publishing, has finally decided to try her hand at being an administrative assistant to the most powerful person in fashion Miranda Priestly (an odd entry level position, but there it is). This is despite her goals of doing “real” journalism and finding fashion a ditzy girl’s game. At this point, Andy is poor, dating a line cook, hanging out with other friends who hate their j-o-b-s and who early on in the film toast to the notion of “jobs that pay the rent.”

Andy gets the assistance job, obeying every whim of Runway magazine’s leader Priestly (played famously by Meryl Streep). And the whims are, from the beginning, regularly impossible for all but the most intrepid and dedicated assistants. Andy begins her journey wearing the frumpy uniform of Northwestern University smart people who see themselves as above fashion, a uniform she pulls over her porcine size six body. But after a couple of rants about the importance of fashion made in her direction, and after the realization that Priestly will never acknowledge Andy’s successes as long as Andy refuses to respect fashion, the young protagonist dons the Versace and Jimmy Choos to fit into this new role, even working herself down to a size four (which gets her a celebratory toast from Runway’s art director).

This metamorphosis creates the strongest emotional tones in the entire film. Andy emerges confident, sexy, powerful. This is euphoric. Andy, along with the viewers, drink in with delight the shocked look on her coworkers’ faces (who only minutes of runtime earlier were snickering at Andy as a walking, talking faux pas). This new wardrobe prints the ticket for her acceptance into the fashion world. Now she has respect as she runs errands for Priestly that trace through the world of high society, including a “real” journalist who tries to bed the well dressed Andy and even asks her to send him some of her writing. It appears that by shedding her old self who was too focused on “real” journalism to be concerned with petty things like style, she acquires the tool to enter the realm of “real” journalism — that tool being style.

In summary, fashion (the ultimate class signifier) gives her purchase into the chic realms of the culture-generating bourgeoisie.

Meanwhile, hangouts with her old group of friends take on an increasingly bitter tone. They resent her constantly being late due to work, leaving early due to work, not showing up at all to her boyfriend’s birthday party due to work. So for a while the film jumps between the swirling adventure and excitement of the fashionista set to the resentment of the working class who stupidly continue in their proletarian existence without understanding the hard work Andy does.

The climax, of course, is that Priestly’s sociopathy knows no bounds, and when Andy finally confronts this in an extraordinary manner, she abandons Priestly and reconnects to her boyfriend. Thus, she realizes that there are things more important in life, yadda yadda, so on and so forth.

At the end, as she is interviewing for a “real” journalism job (though still dressed to the 9’s, proof not all was for naught), her prospective employer tells her that Priestly faxed a resounding endorsement (not all for naught indeed). Despite everything, the mother figure really did respect daughter though she did not openly admit it, and through the power of the mother, Andy gets what she wanted all along. [1]

The Devil Wears Prada is not about the cruelty of the fashion world and the importance of staying true to who you are. It is about the necessity of the fashion world (including the cruelty of it) and the importance of adjusting who you are to meet its expectations. By impressing the fashion world (mother), doors will open up for you. But that isn’t even the true moral of the story.

Film is an emotionally resonant art. And the emotions it creates stick with you long after the nuts and bolts of the plot and what the plot is “trying to say” dim in the memory of the viewer. The memory of the emotions might fade and simplify, might coalesce around a general feeling, but that simplified feeling imprints. That’s why you remember how exciting Indiana Jones is even though you haven’t watched it since you were eight years old.

For the majority of The Devil Wears Prada, the emotion is one of intoxication felt when entering the realm of high society. While the particulars of the story locate the viewer inside fashion, it is still a move into the world of the bourgeoisie. That is the main emotional impact of the film, and also the promise of the trailer, which focuses entirely on the protagonist’s makeover/ascendancy and the charismatic dictatorship of Priestly (there are maybe two or three seconds devoted otherwise). That is because the draw of the film is entirely in the vicarious glee we viewers feel to witness a commoner like us (albeit a well educated commoner) gain access to the upper echelon of society.

Andy’s newfound powers after her makeover are one expression of the thrill, but consider the love of Priestly’s character. She is cold, demanding, unapologetic. The entire office trembles at the news that Priestly will be arriving early one morning, and they scramble to reshape the space to her exacting preferences. An entire industry watches her face for the smallest tics (raised eyebrow, pursed lips) to determine the trajectories of careers and the trends of the upcoming season. Priestly’s role is not to show the rise to power, it is to show unbridled power long since secured. Viewers love her character because there is nothing quite so intoxicating as imagining yourself with such control over the world around you all while immaculately dressed and quaffed. She shows us who Andy could become if only the pesky little cinematic necessities of having a protagonist “grow” and do the “right thing” didn’t make up the last reel. She is the way we get to eat our cake and stay a size four. Andy takes us from where we are to where we want to be, and while she has to “grow” and give up the pleasures of the life we want, we get that story of keeping the life too, in the form of Miranda Priestly. In one of their final exchanges, Priestly tells Andy that she sees a lot of herself in the young assistant, an implicit promise that if we don’t like the ending, we could imagine ourselves continuing on with the devil and one day filling her Prada.

In this way, the film is a female power fantasy. It’s about the intoxication of class in our society from a female perspective.

Here is where one could insert a rant about neoliberalism and how its subjects are psychically led on through their miserable lives by the empty promise of class mobility. Perhaps. Maybe there is something to that. But I think more than this, there is a deep truth about class being explicated here. Sexiness, power, influence, glamour are not being lied about here (of course there is a class mobility lie here, though Andy is from a prestigious university anyway). These are desirable states, and these are the definitional grounds by which class operates on the level of personal expression (of course, every good little Marxist knows class operates fundamentally around ownership of the means of production, but let’s hold off an analysis of Capital Volume I for a different 2000 word blog post). The Devil Wears Prada offers people who do not have access to those states some spectral whiff of the good life. Furthermore, it does so by giving Andy the most stereotypical female form of ladder climbing: she succeeds as the over-achiever — but one who actually gets somewhere through that form of hard work.

Andy’s character is that same gold star, all A’s, nervous energy fueled female character we’ve seen time and again, but her success as the tenacious secretary builds a bridge over to the opposite form of female success in a patriarchal society: sexual desirability and fashion sense. What if wearing Dolce & Gabana was the homework assignment? What if knowing the history of cerulean blue fabrics was the essay topic? What would a 4.0 grade point average look like in that world?

The original Andy, with her sterling academic record and college paper journalism, is blocked off from a major element of female expression and the female sphere in our society (i.e. fashion). But it is through the very same tenacity and direction that got her one kind of success that she is able to have it all. And what is her reward for conquering both roads to feminine success? Membership in high society.

The Devil Wears Prada is, purposefully or otherwise, about the limitations of female power, the taking of power in ways culturally codified as “feminine”, and about the intoxicating rush of jumping class division and gaining that feminine form of power. While the film may not necessarily critique the limitations of female roles inside of our society nor the class divisions (a division it sends its protagonist magically hurtling over), it does trade in these facts about our society. No, it is not a proletarian feminist film. But in its lack of critique it ends up accidentally saying a lot of what a film with such political goals might, only with inverse values. And, but inverting the values, ends up accidentally revealing a lot more about the dominant ideology than any politically-motivated film could.

[1] It is interesting that, given Priestly’s role as the mother-figure, Andy’s success in college is related to approval from the Father. But for Andy to fully self actualize and thus succeed in “real journalism”, she needs to return to the Mother’s realm of the feminine (fashion) and get approval. Once she has both of these, she can proceed through the door to her “real self” as a “real journalist”.

I recently made the mistake of reading critical reviews of Ari Aster’s film Midsommar. I’ve written about this movie before, and as you might have gathered from my words about it, I loved it. Some critics did not. And that’s okay. It isn’t imperative that everyone recognize undeniable artistic genius when they see it. What I noticed about these criticisms, however, was something that creeps up constantly in the gargantuan amount of video essays and blog posts about film pumped out every month: using studio expectations of what films need as the yardstick for whether a film is good or bad.

“Grim, grisly and downright sickening, Midsommar is a feel-bad horror film about suicide, mercy killings, insanity, graphic nudity, religious hysteria, and the kind of grotesque imagery that exists for no other reason than shock value. Director Ari Aster’s delusional fantasy films contain enough imagination for today’s pretentious critics to label him a ‘visionary,’ but not enough substance or ideas for the real world to regard him as an artist of true and lasting value...

This film seems endless, with all of the horror restricted to beginning and end sequences...”

[Note: I’m not going to address how many critics completely misread the pagan community Hårga in Misdommar. That is another discussion altogether, and my previous writing on the film (linked at the beginning and appearing directly below this post) covers enough of the topic that going into audience reception of Hårga would retread too much to make it worth anyone’s time.]

Edward Hopper’s New York Movie (1939)

Anyone who has written a screenplay, and therefore sought out advice on how its done, knows how cynical a market it is. Almost all screenplays purchased and produced in the United States adhere to a uniform plot structure, with each plot point appearing on or near the same page in each script. Protagonists encounter a call to action, refuse it, become convinced, reach a midpoint where there is no turning back, hit a wall and decide they can’t reach their goal, are forced to return to their journey, and make a final push in the climax. Protagonists need to have agency and must develop. All major plot twists need proper set-ups. Etcetera, etcetera, so on and so on.

Many of these story features work well most of the time. That’s why this structure has become industry standard in Hollywood: if a screenplay fits into that mold, it will work as a story.

Of course, the problem of demanding this strict format industry-wide has clear implications. Slowly, films produced move more and more into a center line, and most films become simple reskins of the same story. This is all bad and terrible and what not, but that’s not what we are concerned with here. What I’m even more concerned with is how this is generating a language inside of the viewers themselves that limits their ability to see films that decide to work in a different way.

When these rigid expectations are broken, middle brow viewers who are half-trained in this notion of film believe those breaks to be mistakes rather than choices. The consumption of criticism that is built around these studio expectations ends up constituting the filter by which the consumers of this criticism begin to process films. It is a case of viewers who are both too well and not well enough educated in the discourse.

From Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979)

Going forward, the depth of this mistake might be hard to see. But considered against works from the past, we see how quickly these concepts break down. Take for instance, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, one of the greatest films ever made (and a film I will likely write about in the future). Almost all of the decisions characters make in the film that have any real impact or consequence happen before the beginning of the film, with a small number of exceptions. Large swaths of runtime are devoted to situating the viewer in the mysterious Zone or the future Russia. Pipes dripping water, a train rumbling, people smoking outside a bar, water running over abandoned items both sacred and profane. Time is devoted to putting the viewer in a place. No, nothing is happening. There is no character development going on. There is no conflict. There are only compelling images that relate the world and reflect the truth of ours.

That isn’t a flaw. It isn’t that Tarkovsky didn’t know what he was doing. It isn’t that they wanted to stretch a thirty page script into a three hour movie. This tonal decision does not fit into Hollywood’s strictures of what a film needs to be doing, but it leads to a film far greater than just about anything Hollywood can achieve using its current system.

Akira Kurosawa on the set of Ran (1985)

And this seems almost naive to write about, but a strange phenomenon is occurring alongside and in tandem with the one described above where a cynical outlook on how a screenplay ought to function according to film producers is now considered the adult one. The over-correction against romantic notions of art as an intuitive process that flows from the muse through the artist and into the world has reached an apex where any defense of intuition and non-systematic filmmaking is seen as childish, naive, not serious. It is seen as somehow shrewd to know that a film needs these certain elements, that a film couldn’t be good without them, that their lack can only exist as a flaw and not a feature.

The truth on the other side is that filmmaking is a unique art form in that it often requires huge sums of money and large groups of people to accomplish, and therefore it is not reasonable to expect all of those resources to go into a project that relies on trusting an individual’s artistic vision. Here opens a side argument for the artistic productivity of state funded film programs with missions focused on cultural production and not high returns, but for our purposes here it is to elucidate just what inside this line of thinking is true, because that truth gives the mindset power. But when carefully looked over it is clear that the purpose of these rigid guidelines is a pecuniary one rather than an aesthetic one.

Of course, everyone is allowed to like what they like, and if you prefer films that stick to this Hollywood style, that is A-OK. But it is this reverse use of the style that is troubling. To see people being trained to dismiss films solely on the basis that they break from this style is a part of a continuing devolution and middlebrowing of our culture. And sure, something like character agency can help you identify why you aren’t connecting to a story, but to seek it out as an item on a checklist and docking points whenever a film leaves it unchecked is the exact perversity outlined above.

The original Suspiria by Dario Argento is a masterpiece of horror cinema. For myself, watching the movie at eighteen sent me down a path of foreign horror films, then foreign films in general, and so opened the universe of great cinema to me. It played such a pivotal role in my personal aesthetic development that the announcement of a coming remake had me feeling two kinds of ways: incredible interest at how the filmmakers would attempt to take a second bite at the apple, and incredible wariness at just what we could expect. Argento’s Suspiria did not seem to me the kind of film you watch and say, “They could have done better. Someone else should take a shot at it.”

It’s worth mentioning that in the last two decades (the length of my film consciousness) there have been a spat of horror classic remakes that were all either bad (like Alaxendre Aja’s The Hills Have Eyes) or, at best, shot-for-shot remakes (like Rob Zombie’s Halloween). The one exception, perhaps, was Zack Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead, but that film now has the dubious honor of spawning the zombie over-saturation wave that came ten years later — along with Danny Boyle’s zombie-like 28 Days Later. So all the signs pointed to a Suspiria remake being less than good work.

When I finally watched it, I was happily surprised.

What Luca Guadagnino et al achieved was that most difficult task of reenvisioning without abandoning. The new incarnation takes the bare bones of the source material and creates an entirely different kind of horror experience, while still drawing enough one-to-one echoes to feel like a kindred spirit.

Argento’s film uses a neon baroque sensibility to create a world where the characters, story, and logic function on a dreamlike, “oneiric” level — a literal nightmare. Guadagnino’s film switches out the high saturation for a muted, realist palette evoking a divided Berlin at the center of world history, and he switches out the baroque with the modernist. These two underlying aesthetic guidelines travel throughout the remake, and provide a lens with which to see on what terms the two films function. It also provides a guideline to keep the film on its own terms while borrowing from its source.

Carrying out a revived aesthetic (like mid-century modernism) is always a balancing act. The visual references must drive all the way up to the line before crossing over into pastiche. That is, every reference must function meaningfully, must express, must convey information. To the degree a reference satisfies these needs, it escapes pastiche. To the degree it fails, and exists merely as a reference, it is pastiche. For Guadagnino’s remake, there were thus two horizons where this danger existed: reference to the original film, and reference to the guiding aesthetic of modernism.

Guadagnino himself claims that he hopes to have no style, but his Suspiria undeniably does. It uses the visual language of modernism to describe the unsettling logic contained within the coven of witches, a brooding and dangerous situation inside Cold War Berlin (a different kind of brooding and dangerous situation).

We use style to forget ourselves. To eliminate our viewpoint and merge into a reference structure handed to us by a social network. By engaging the style, we join that network and influence the very substrate we are relying on to be separate from ourselves, but this is of little consequence inside the gestation and creation because you don’t join that conversation until it has already influenced your utterance — by the time people see your film, you’ve already made it.

In this way, Guadagnino used style much like source material, two reference patterns working in tandem. His Suspiria is conceptually elevated then, because it has so many added layers of discussion. It speaks with history, with its predecessor, with the audience — even with witches.

And while this kind of referencing can go very wrong (see the general culture right now as it feeds on both a blockbuster film based on the early 90’s video game Sonic the Hedgehog and a live-action children’s mystery starring a character from a popular 90’s trading card game and anime), when we see it work as it does in Suspiria, we see the potential fertility of cannibalizing the past.

How does his film succeed? For one, the deliberate pacing works to its advantage. With so many masters to serve (and it seems to freely add to this list by engaging in excessive world building both in historical and geographic context as well as the fantastical mythology), the film needs time. And let me tell you, it takes it. The film runs for two hours and thirty-two minutes, which is absolutely gargantuan for a horror film. But this time means that no reference needs to stand without support. This is not a simple recombination of signs. There are multiple characters able to pass the through the world, interact, and build a reality inside of the sets and the story. That pacing is the precise antidote for the problems with a culture that has begun to recombine symbols rather than create new myths. Recombination is interesting but thin, so a culture relying on it to generate itself needs rapid production of new combinations. The more you sit with a reference, the more people think, and so something has to stand behind it if your camera lingers over it.

The second way that the film succeeds is more quaint and old fashioned, but it gives us a clue about a good test for a work that relies on references and is embedded in an entire network of style. That is: does the film work if it weren’t evoking the original? Yes. The Suspiria remake goes it alone enough to prove itself, particularly in areas that are the easiest to exploit for nostalgia, like musical themes and iconic shots. The one sin of nostalgia exploitation the remake commits is using the lead actress from the original (Jessica Harper) for a cameo. But the fact that they resisted using the iconic theme of the original and remaking any of the famous death scenes absolves them if there be any justice in this world.

What I took away from the experience of 2018’s Suspiria was a renewed interest in the zeitgeist-dominating nostalgia spectacles over which so much cultural critics’ ink has been spilled. Sure, I noticed it, even hated it, even used it as a symptom to diagnose a terminal cultural disease embedded in late capitalism. Once I’d seen a nostalgic remake done correctly, it all meant so much more. If it were all bad, it would be inherent, inescapable. But remakes can be done well. Our warm and fuzzy cinematic memories can be used and manipulated for new purposes in a productive, generative way.

That means there is more to the story. Cannibalizing the Past is a series of observations on that story.